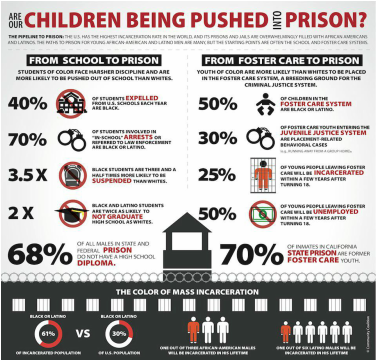

Children Being Pushed into Prison from the Community Coalition Children Being Pushed into Prison from the Community Coalition “Come at me, bro!’ I teased while helping a freshman boy a few months ago. Albert and I giggled as we discussed the dialogue in the narrative he was writing. The classroom was calm and filled with students writing in nooks or in small groups. It was completely normal day in my English class. But, that sentence. That’s all it took. Suddenly, Albert was towering over my chair yelling, cursing, and threatening me. I felt the angry spit of his words hit my face. I could have responded to Albert by following California’s current laws on student discipline. I could have stood up, placed my hands on my hips, waved a finger in his face, scolded his outburst, threatened suspension, and shouted at him to “Get out of my classroom!” as I pointed toward the door. I could have easily pushed him further into what Kemerer and Sansom (2013) explain is known as a “Big Five” action. But, I did not. Instead, I remained seated, sat still, and calmly said, “I’m sorry. I was joking. Calm down. Take a walk.” Even though Albert did not follow through on the threats he voiced, he violated California Education Code 48900(a)(1) because he “threatened to cause physical injury to another person” (Kermer and Sansom, 2013). He could have been suspended, even if it was his first offense. Education codes, such as this one, do not reflect positive behavior intervention supports and trauma informed care. They do not require teachers to identify traumatized students nor do they hold teachers accountable for triggering students or their role in the escalation of “Big Five” behaviors. Instead, they hold students, like Albert, accountable for knowing and abiding by written schoolwide behavior guidelines--regardless of whether or not they know how to read or demonstrate the desired behaviors. Most current California discipline laws are pushing our most underserved and disadvantaged youth from one learning environment to another until many are eventually driven into detention facilities or just out of school altogether. By the time this happens, many students, including many of my high school students at San Pasqual Academy, a residential high school for foster youth, demonstrate significant gaps in their academic and social emotional skills. Based on my informal conversations, approximately the majority of my students have been suspended and a handful have been expelled. This aligns with the claim from the report “Ready to Succeed” from the Stuart Foundation, which claims California’s “Foster youth are suspended at rates nearly triple to the general population” (2011). Eventually, these students continue down what Amurao explains is known as the “school-to-prison pipeline”: 25% of young people leaving foster care will be incarcerated within a few years of turning eighteen” and “70% of inmates in California state prison are former foster care youth.” Suspension rates are not the only contributing factor in the prison pipeline--race, poverty, and adverse childhood experiences--all fuel the drive. But, educators can control the suspensions. Fortunately, a California has passed an assembly bill to address the suspension rates. The report “State Schools Chief Tom Torlakson Reports Significant Drops in Suspensions and Expulsions for Second Year in a Row” from the California Department of Education (2015) explains, “Willful defiance became identified with the problem of high rates of expulsions and suspensions after the CDE reported a high number of minority students were suspended for this cause. Those figures helped spur the passage of Assembly Bill 420, supported by the CDE and sponsored by former Assembly member Roger Dickinson. The bill, signed into law last year, limits suspensions and expulsions for disruptive behavior in certain grades.” As California schools work toward meeting the goals of AB 420, they are implementing systems such as positive behavior intervention supports (PBIS) and restorative justice practices. My district is using local control funding formula (LCFF) to decrease suspension rates. Goal One Action D of the San Diego County Office of Education LCFF aims to “Continue to provide and monitor initial implementation of professional learning for staff on PBIS, trauma informed care and Restorative Justice” (SDCOE). My site was an early adopter of PBIS and is currently working with a coach to integrate restorative justice practices into our interventions. Instead of simply following California law on student discipline, we focus on teaching our students how to behave. In order for this to succeed, teachers and students need to work together to learn how to create a positive learning community. Back to Albert towering over me. Within a few seconds, he simply walked out of the room. I thanked his classmates for remaining calm and listened as they informally debriefed. Within a few seconds, the classroom was again peaceful and productive. I called the school office to notify the staff that Albert had left on a stress walk; he was already in the office debriefing (and crying) with a residential staff member. Albert was not suspended. After school that day, he politely asked to speak with me in private; he offered a sincere apology and admitted that he could not even remember what happened. I accepted his apology, praised him for walking out, and thanked him for coming back to apologize. I also encouraged him to continue working with adults to identify his triggers and manage his responses. He agreed and has since demonstrated significant growth. Just today, Albert sat next to me in class and giggled with me as I helped him edit a project about his future career in law enforcement. Teaching students how to behave will keep students, like Albert, out of the school-to-prison pipeline. Works Cited Amurao, C. (2011). Fact Sheet: How Bad Is the School-to-Prison Pipeline? Retrieved July 18, 2015, from http://www.pbs.org/wnet/tavissmiley/tsr/education-under-arrest/school-to-prison-pipeline-fact-sheet/ Kemerer, F., &; Sansom, P. (2013). California School Law Third Edition. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press. Ready to Succeed. (2011). Retrieved July 18, 2015, from http://www.stuartfoundation.org/OurStrategy/vulnerableYouthInChildWelfare/Initiatives/ReadyToSucceed SDCOE's Local Control and Accountability Plan. (2015). Retrieved July 18, 2015, from http://www.sdcoe.net/about-sdcoe/Pages/Local-Control-Accountability-Plan.aspx Suspension and Expulsion Rates for '13-14 - Year 2015 (CA Dept of Education). (2015, January 14). Retrieved July 18, 2015.  I learned a lot more than style at summer camp! I learned a lot more than style at summer camp! Fifteen years ago, I was pushed into having my first series of courageous conversations with an employee. I was a unit leader at Camp Whispering Oaks, a Girl Scouts resident camp in Julian. After just the first week of camp, our administrative team identified that one of the new counselors was significantly struggling to fulfil her duties and transition from the role of camper to staff. They placed her in my unit and asked me to give her specific daily goals, observe her performance, and then meet with her to debrief the day. I also had to report to the camp director daily to share her progress. In our nightly meetings, I sincerely tried to help her understand her specific successes and areas of improvement. I also helped prepare her for the following day. The counselor made small improvements, but she was still unable to function at the same level as the rest of my unit. The director decided to terminate her position at the end of the week. As a result of this experience, I learned that courageous conversations can support both the growth and dismissal of an employee. As a teacher, I have been pushed to have courageous conversations about the dismissal of employees. However, my motivation for these conversations often originates out of concern for the well-being of my students, my coworkers, and myself instead of from the guidance of a direct supervisor. My first courageous conversation as an educator occurred a few years ago when I nervously walked into our executive director’s office holding a list of evidence in my shaky hands. I explained that I was there to ask for her help because I did not know what else to do. Aside from simply being unorganized, ineffective, and abrasive, my current principal demonstrated immoral and harassing behavior. I shared examples of his inappropriate behavior in front of students, staff and partners. He laughed as he referred a female student’s crotch as a “cockpit” in the middle of a staff meeting. He eagerly told campus visitors a story about catching two students leaving a dumpster area and candidly shared his thoughts about teenagers having sex in the trash. He disciplined students with a Bible on his desk. After repeatedly pushing away his hugs and telling him to not hug me, he began coming into my classroom to hug me in front of my students. He repeatedly called me into his office to discuss topics such as his pretty teacher theory: he believed students were more eager to learn and demonstrated more acceptable behaviors in the classrooms of pretty teachers as opposed to regular teachers. He considered me one of the pretty teachers. The morning after I received a scholarship on the field at Petco Park, he called me into his office to tell me that he had received multiple complaints from partners that I was preaching homosexuality in my classroom, which I later discovered was a blatant lie. But, after driving to work beaming with pride that morning, I walked out of his office to start my class in tears. Eventually, I followed the encouragement of my colleagues and told the executive these and many, many other examples of his inappropriate conduct. I reminded her that my campus is filled with victims of verbal and sexual abuse and explained how was exploiting this by leading through intimidation. She listened. After each member of our staff individually spoke with her and then a lawyer, the principal was removed from our school. But, he was not fired. Instead, he was placed in a stand-alone, coed, independent study classroom in another part of the district. As I read about the dismissal procedures for permanent teachers and administrators in California School Law: Third Edition by Frank Kermer and Peter Sansom, memories of this experience stirred in my mind. According to Kermer and Sansom, permanent or probationary teachers can be dismissed for immoral or unprofessional conduct and evident unfitness for service (2013). But, this man was not a teacher. As an administrator, he did “not have the right to a due process hearing prior to dismissal, release, or reassignment to a nonadministrative position. However, [he} ... retain[ed] permanent status to a previously held certificated or classified position” (Kermer & Sansom, 2013). Unfortunately, he was a home-grown principal and had taught in our school district for many years prior to becoming an principal. I do not understand how someone who had demonstrated such immoral conduct and evident unfitness, as validated by corroborating examples provided by almost the entire certificated and classified staff of my site, was not fired. If he was a teacher, his behavior would have been grounds for dismissal. Instead, he was simply handed a new set of students and coworkers. Looking back, I was able to have this courageous conversation because I knew the risk was necessary to protect my students, my colleagues, and myself. I know that even when they are spoken with a shaky voice, courageous conversations are necessary. Works Cited Kemerer, F., & Sansom, P. (2013). Employment. In California School Law Third Edition. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press. San Diego County Office of Education Board Meeting, June 10, 2015 San Diego Unified School District Board Meeting, June 2 , 2015 Fifteen years ago, I served as the student board representative for my school district. All I can really remember is being entertained by emotional parent complaints and listening to jargon-filled presentations. Upon receiving my first pink slip from that same district seven years later, I spoke at a school board meeting for the first time. Three years later, I was motivated by another pink slip to speak in front of a school board--this time as a teacher in my current school district, San Diego County Office of Education (SDCOE) Juvenile Court and Community Schools (JCCS).

Since that first pink slip scare with JCCS, I have been a regular attendee at SDCOE board meetings. I try my best to pay attention and even take notes when JCCS is on the agenda. I have spoken on behalf of my students and coworkers and even helped to introduce my site’s student board representative. However, I honestly spend most of the meetings bored by detailed presentations about programs far removed from my classroom or confused by topics that I do not completely understand. However, I keep attending. During the past few weeks, I attended the San Diego Unified School District (SDUSD) June 2 meeting and the SDCOE June 10 meeting. After observing a board meeting in a traditional school district for the first time in ten years, I was reminded of the strong parent and community voice that is often shared during board meetings in local districts. On the other hand county board meetings are often filled with presentations about broad programs that serve students across multiple school districts. And, many of the students in the district SDCOE directly oversees, JCCS, are incarcerated, on probation, homeless, and/or foster youth. The parents of these students are generally less involved in their students’ education than parents in traditional districts. Since the roles of local districts and county offices are already different in nature, I am focusing my attention on the behavior of the school board members instead of the content of the meeting. When I first began attending SDCOE board meetings, the board members said very little. One memorable member was notorious for actually falling asleep during meetings. I remember giggling on more than one occasion when he fell asleep while watching a PowerPoint and then failed to turn his chair back to face the audience instead of the screen on a back wall. Even though the SDUSD school board members were all able to stay awake for the duration of their meeting, some might as well have been sleeping. They diligently took notes, shuffled papers, and appeared to be actively listening, but they were very quiet. Of course, they could respond to the public comments which consumed approximately half of the meeting time, but they also said very little in response to the other agenda items. When they did speak, most of their responses simply congratulated the presenter. For example, when Lee Dulgeroff, Chief, Facilities Planning and Construction concluded his presentation, about Propositions S and Z Project Plan, he was simply thanked for his hard work. He was not challenged or asked to elaborate. Unfortunately, I have repeatedly observed similar behavior during SDCOE board meetings. Presenters share slides and data about complex topics, from funding to test scores. It is unreasonable for all of the board members to be experts in every area. However, instead of asking questions to challenge, clarify, or make connections to the information, the board members often just nod and thank the speaker. I have sat back and watched as presenters simply slide things through, such as when JCCS Executive Director posted a slide that read, “Continuity of San Pasqual Academy principal,” without elaborating on it. My school had just hired its third principal in six months--she was sitting in the front row. But, the vague slide made it appear as if continuity had been established. Moments like this make me wonder if the board is paying attention, if they comprehend what is being said, or if they even care. As elected officials, I expect board members to take time to analyze agenda items and hold the presenters accountable by asking challenging questions instead of just smiling and nodding--especially when they represent students whose parents are unwilling or unable to attend meetings to speak on behalf of their children. Within the last year, newly elected members of the SDCOE board have begun asking complex questions at the end of presentations. Gregg Robinson leads this questioning and usually notes that he has previously reviewed the material being presented. In response to his questions, the presenter often directly responds or pulls a colleague from the audience to provide specific details. At this month’s meeting, Robinson demonstrated this by questioning Senior Director of Learning and Leadership Karla Groth at the conclusion of her presentation about Countywide Common Core and Performance Tasks in English Language Arts and Mathematics. Her presentation discussed the process of implementing and scoring performance tasks. However, when Robinson directly asked her for the assessment data, she said the English Language Arts results were posted on the website and began speaking about the process. He eventually directly asked, “Can you quantify that?” She replied with a “no” and began speaking about the process again. It is alarming that an entire presentation was made about assessments which omitted a direct statement of the results, and only one board member seemed to have noticed. Robinson’s preparedness, attentiveness, and outspoken inquiry demonstrate that he takes his responsibility as an elected official seriously and genuinely cares about public education. In contrast to being passive listeners during meetings, I have noticed that board members often only become candid and engaged when conversations deviate from official business. At the end of Dulgeroff’s presentation about the Propositions S and Z Project Plan during the SDUSD meeting, Board President Marne Foster asked a clarifying question about the date of a ribbon-cutting. After Dulgeroff responded, Foster candidly announced that the date was the same as another board member’s birthday. Her question was meant to entertain and bring attention back to the board members instead of deepening her understanding of the presented materials. This was not the first time a birthday came up during the meeting. During public comments at the beginning of the meeting, Foster’s family joined the queue of speakers to present Foster with roses and sing “Happy Birthday” to her. Even though this created a lighthearted moment the setting was completely inappropriate. Many concerned citizens, parents, and even students had just finished sharing concerns about transportation being cut to charter and magnet schools and field use policies for non-school use. Many speakers were cut off for exceeding their time limit--including elementary students. However, the meeting came to a halt when the roses were presented to Foster’s seat. Board members smiled in support, but this was incredibly disrespectful toward those who had just spoken. The public had used their limited time to voice genuine concerns, but more attention was given to flowers. Unfortunately, this reminded me of SDCOE board meeting. At the end of SDCOE meetings, each board member is given a few minutes to share a report about his/her individual experiences of the past month. Lately, members have been speaking about visits to school sites, attending conferences, and communications with JCCS teachers. But, personal comments often seep in. On late nights after sitting through more than two or three hours of presentations and comments, I have wriggled in my chair while listening to board members speak about their hobbies--including stargazing and car clubs--instead of the students and staff they serve. Though this has begun to decrease with the current elected board, at this month’s meeting one board member tearfully announced that he had just become a grandfather. I appreciate how sharing personal moments help the SDUSD and SDCOE board members to appear more personal. However, this practice in unprofessional and inconsiderate of the speakers and audience members’ time. Often, the only time board members abandon their stoic expressions, smile, and make eye contact with the audience as they speak about their personal lives. Although I doubt it is intentional, this sends a message that they are not passionate about the work they are elected to do and seem to take relish the spotlight. I wish the passion board members share when speaking about their personal lives was instead channeled into a passion for the students, educators, and communities they serve.  Late Night ASB Advisor Trip to Home Depot Late Night ASB Advisor Trip to Home Depot Chicken wire, gumdrops, tiaras, helium tanks, dowels, megaphones, floating candles, marshmallows, fishing line, and hundreds of candy bars. As Associated Student Body (ASB) Advisor at San Pasqual Academy (SPA), I have submitted reimbursement receipts for thousands of dollars in concession stand inventory and event supplies this year. Student body organizations, such as my school’s ASB, are so complex that even an expert independent audit would not be able to detect fraud. The audit findings may give a positive qualified opinion or notice that the organization does not follow generally accepted accounting practices, but it would be nearly impossible for anyone besides a school’s ASB advisor and ASB officers to track and justify every single expenditure--especially of consumable goods. ASB finance management at my school needs improvement in order to pass an audit or even to simply prepare to respond to potential accusations of fraud. According to Townley & Schmieder-Ramirez (2015), “A school district's governing board, the superintendent, business manager, and principal have major roles to perform in effective management of a student body organization.” However, in my role as a new ASB advisor, I only communicated with my principal and our student support specialist about ASB finances. At the beginning of the year, my principal gave me a constitution that provided a generic overview of how to handle finances but contained gaps, such as a description of the treasurer's responsibilities. I was given a form to use for cash boxes and reimbursements from our ASB bank account (controlled by our student support specialist and principal) and reminded to have students take minutes of meetings. I was not told how much money was in my account but was told the district had money set aside for supplies. Although I was continually frustrated by a the reimbursement system that required me to spend thousands of dollars out of my own pocket (last year’s advisor had a credit card), lack of my ability access a running balance of the account, and never learning how to access the money I was told the district provided, this system worked for the year. After reading “Student Body Organizations” in School Finance: A California Perspective by Townley & Schmieder-Ramirez I have created a suggested plan of steps that can be taken within the next few months to strengthen the finance system of SPA’s ASB. The ASB advisor and principal can:

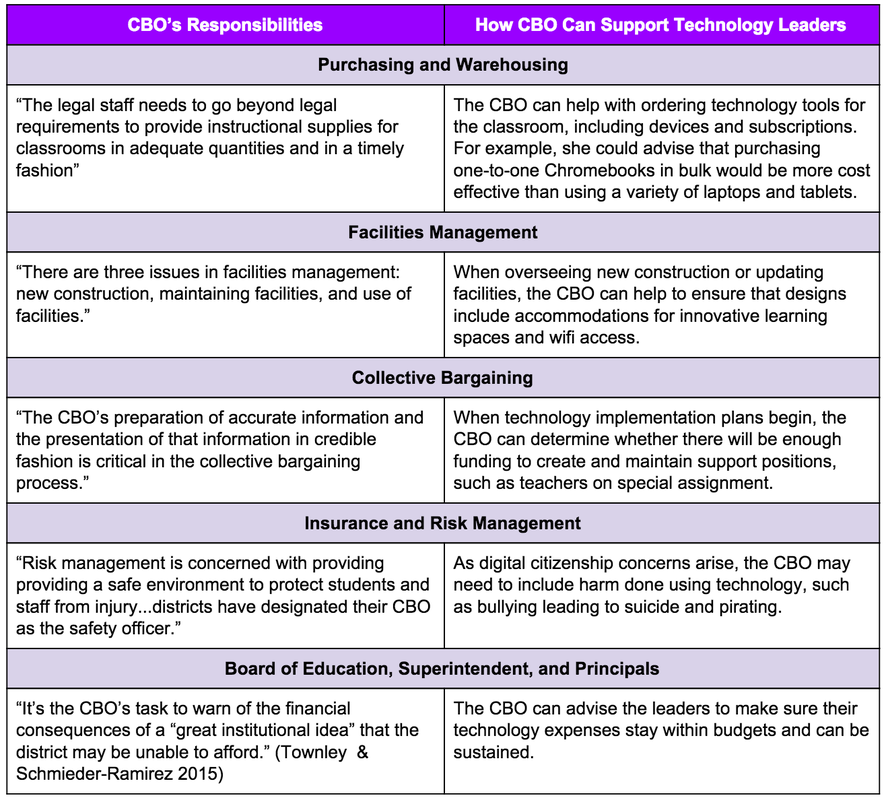

Works Cited Townley, A. J. & Schmieder-Ramirez, J. H.,. (2005). School finance: a California perspective. Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt Pub. Co. CBO’s Negative Impact on a Shop Class and Potential Positive Impact on Educational Technology6/12/2015 Even though I have sat through hours of San Diego County Office of Education board meetings attempting to follow presentations made by our district’s CBO (and our professor) Lora Duzyk, she is not the first CBO to come to mind. My father teaches in a small unified school district in East County San Diego. For the past few years, many of our conversations have involved stories sharing his frustration with his district’s former CBO. My dad teaches shop classes. When he began his program, it was funded by the Regional Occupation Program (ROP). The CBO shared the annual budget with him. As a result, he was able to purchase the latest, and safest, tools and plan projects for his students by dividing his annual budget by his enrollment. To purchase supplies for his woodshop and metalshop classes, the CBO provided him with a credit card that pulled directly from his ROP budget. He voluntarily used his own truck, trailer, and gas to drive down the hill to purchase large orders. If he needed last-minute supplies, he could run to the local family-owned hardware store to purchase using an account established by the CBO. However, a few years ago, this changed when his small district’s superintendent (who was later fired for sexual harassment and eventually involved in scandals in two other districts) hired a new CBO. Under this business office’s management, my father and his ROP colleagues were not given annual budget reports. When he inquired about how much money was in his budget for the year, the CBO responded by saying, “How much do you need?’” As a result, he struggled to complete long-term curriculum maps and often had to ration his supplies. He was unable to quickly replace and repair broken tools. Additionally, the purchasing process became very complicated. He often had to beg for funding, even though his shop repeatedly came to a standstill because students were out of basic supplies, such as plywood. When he was given a purchase order, he took it with him to Home Depot to shop; afterward, his superintendent stopped by the store on his way home from work to pay using his district credit card. A new superintendent was hired, but the ROP program’s frustrations continued. Under the leadership of this superintendent, extra money began to funnel into the high school athletics programs. At school board meetings, the CBO made presentations in which large quantities of money appeared budget lines titled, “Other Expenses.” The school board and superintendent just smiled and praised the CBO for her hard work instead of asking questions about how these funds were spent. My father’s relationship with the CBO did not change, but he began hearing whispers from the business office staff that the ROP “other expenses” had been used to purchase new goal posts for the football field and to resurface a gym wall. Within the last year, the CBO was fired. Her replacement has established transparency and is building relationships. The ROP program, now called Career Technical Education, receives an annual budget. The teachers in the program decide how the money should be spent and they work together to balance large purchases with smaller recurring expenses. The logistics of how to actually shop for supplies is still being worked out, but my father was recently paid his hourly rate to shop on a Saturday and hears the CBO is attempting to reestablish his account with the local hardware store. As a result of the efforts the new CBO has put into working with teachers, this year the students in my father’s shop class have been able to design and build popular projects including trebuchets, coat racks, and tone boxes. As a technology leader, I will not need to run to Home Depot in the middle of the week--well, at least until I am fortunate enough to have a makerspace. However, I will need to work with the CBO to support students. According to Townley & Schmieder-Ramirez (2015), “California’s chief business officials are ‘key players’ in the successful management of a school district.” As a technology leader, I will need to work with the CBO so that they will be able to help me plan ahead and implement plans to increase effective technology use in my school. Works Cited

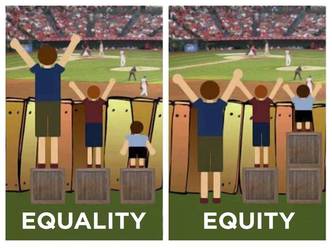

Townley, A. J. & Schmieder-Ramirez, J. H.,. (2005). School finance: a California perspective. Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt Pub. Co.  Equality vs Equity Equality vs Equity Since Serrano v. Priest established that California’s property-tax dependent finance system violated the 14th Amendment to the US Constitution and the Education Clause of the California Constitution, the school finance system has slowly become more equitable. According to Duzyk (2014) the state and local funds that combine to make up a district revenue limits attempt to create equal amount of per pupil funding, but basic aid districts are able to use their extra property taxes to exceed their revenue limits. Even though the revenue limits attempt to make things equal, the wealth of basic aid districts gives their students an inequitable advantage. But the inequity does not just apply to funding sources; districts that receive state and local funds can create inequities in their schools by providing all students with the same supports, regardless of needs that may extend beyond academic skill levels. One type of this population is foster youth. “Mandates” are necessary in order to ensure that our school financial system provides equitable support for special populations. The students at my school, San Pasqual Academy (SPA), a residential high school for foster youth, have plenty of advocates: family court judges, county board of supervisors members, lawyers, Court Appointed Student Advocates, residential agency staff, teachers, mentors, and even biological family members. Even with these advocates, the middle schoolers who live on our campus and attend school off campus at San Pasqual Union (SPU) in the Escondido School District have struggled to thrive at the neighborhood school. However, the relationship between SPA students and SPU has been changing over the past year and the students are succeeding at SPU. Many of our eighth graders are now considering promoting to the off-campus high school down the street with their non-foster youth peers, instead of eagerly leaving to return to the safety of SPA. The frictions between SPA students and SPU really seem to be improving. Of course, this is not just a sudden change of heart of the SPU community or change in the behaviors and academic skills of the SPA middle school students--it is about the money. According to An Overview of the Local Control Funding Formula (2013), under Local Control Funding Formula, “each EL/LI student and foster youth in a district generates an additional 20 percent of the qualifying student’s adjusted grade–span base rate.” SPA’s racially-diverse middle school students who have the ability to easily disrupt class and bring down subgroup score percentages on No Child Left Behind Test are now suddenly valuable. But, this would not have happened unless a state mandate validated the needs of this special population. Due to circumstances beyond the control of any district, special populations, such as foster youth, require additional academic and emotional support to reach the same learning goals as privileged students. Since these groups of students are often challenging in classrooms and in test score reports, it may be easier for districts to ignore and push away these students instead of working to understand and address their needs. Mandates are necessary to ensure districts provide all students with equitable learning opportunities, especially the challenging students. (Original discussion post edited for publication.) References Duzyk, L. (2014, October 30). Budget Crisis. Retrieved June 7, 2015, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C-dySrQwqn8&feature=youtu.be An Overview of the Local Control Funding Formula. (2013, December 8). Retrieved June 7, 2015, from http://lao.ca.gov/reports/2013/edu/lcff/lcff-072913.aspx  SDCOE Board Meeting PC: npriester SDCOE Board Meeting PC: npriester Public Opinion Initiatives impacting public education in California represent the opinions of some Californians. According to Public Policy Institute of California (2014), “Likely voters are disproportionately white. Whites make up only 44% of California’s adult population but represent 62% of the state’s likely voters.” This disparity is not new. It has existed since the funding of public schools began to transition from the local to state level in the 1970s. California Opinion Index (2009) states that in 1978, 83% of the voters were white non-Hispanic but they only represented 68.9% of the state’s population. Even though the discussion around financing public education focuses on low-income and high-income school districts, it is important to remember that race is also tied to these communities. The majority of low income American families are racial minorities (Simms, Fortuny & Henderson, 2009). Their opinions are currently not proportionally represented in voter initiatives. However, the current trend to move control of school district funding back to a local level is providing an avenue to include all community members in making decisions about how school funding is allocated. Judges and Homeowners According to Townley and Schmeider-Ramirez (2015), “During the second half of the 20th century, a series of court decisions, propositions, and legislation resulted in a shift from property taxes to other forms of taxation as the primary source of funds for education in California. This change resulted, to a significant degree, in transferring local control of education to state control.” These changes also benefited homeowners but hurt low-income school districts. California’s schools were established using an unfair financing system based on local property taxes. Since this system operated for more than the first hundred years of California’s statehood with little disruption, it is logical to conclude that public opinion supported this system. However, the courts corrected this mistake in 1968. Serrano vs Priest decided that using property taxes as a primary source of school revenues “violated the right of students to receive an equal education” because the taxes did not provide equal funding for all schools (Townley & Schmeider-Ramirez, 2015). This decision impacted the financing of education by requiring the state to help supplement and balance district funds. The California Supreme Court’s decision followed Serrano’s attorneys’ arguments which were supported by the 14th Amendment of the US Constitution and the Education Clause of the California Constitution rather than popular opinion (Townley & Schmeider-Ramirez, 2015). The court’s decision created challenges for the State of California, but it also supported financing the education of students in low-income communities. As evidenced by the passing of Proposition 13, voters strongly valued property tax cuts in 1978. According to California Opinion Index (2009), 66% of registered voters were homeowners in that year. It is likely that this population supported Howard Jarvis and voted in favor of Proposition 13 without considering its effect on public education. According to Kermer and Sansom (2013), the passing of this proposition “resulted in a centralized system of school finance that slowed the growth of per-pupil expenditures.” It seems the voters were driven by personal financial gains and may have not even looked ahead to evaluate how the cuts to education this proposition produced could negatively impact the their communities. According to Townley and Schmeider-Ramirez (2015), “the nation, state, local community, employers and taxpayers” benefit from education. However, Californians seem unwilling to pay more to support schools. Back to Schools Even though voters seem resistant to increasing statewide taxes to support education, they are willing to support initiatives that move funding control to a local level. Governor Jerry Brown has led this effort in with Proposition 39 which reinstated general obligation bonds to allow school districts to vote to increase local taxes to fund district construction projects (Townley & Schmeider-Ramirez, 2015). Additionally under his leadership, schools are currently able to allocate their funding using Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). Returning control of funding, which still comes from the state, to districts has the potential to include local opinions when deciding how to fund schools. However, in my experiences in my district so far, it seems that more work needs to be done. I recently attended the May 13, 2015 San Diego County Office of Education (SDCOE) Board Meeting during which the SDCOE Local Control Accountability Plan (LCAP) 2015/2016 Update was presented. At the conclusion of the presentation, Board Vice President Gregg Robinson commented that he was surprised and disappointed there were no public comments or questions. The next week, I attended an LCAP training hosted by the California Teachers Association and learned how teacher, parent, and stakeholder opinions should be woven into the plan. I began to understand Dr. Robinson’s frustration; if teachers, parents, and stakeholders were invested in the LCAP, they most likely would have provided opinions at the board meeting. Hopefully, SDCOE can continue to work to bring all of those invested the education of our students into decisions about how to spend our funding. LCFF gives our district the opportunity to be guided by the public opinion of our community--instead of just white homeowners. References Bibliography A digest summarizing The Changing California Electorate. (2009). Retrieved May 31, 2015, from http://www.field.com/fieldpollonline/subscribers/COI-09-Aug-California-Electorate.pdf Just the Facts: California's Likely Voters. (2014, August 1). Retrieved May 31, 2015, from http://www.ppic.org/main/publication_show.asp?i=255 Kemerer, F., &; Sansom, P. (2013). California School Law Third Edition. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press. Simms, M. C., Fortuny, K., &; Henderson, E. (2009). Racial and Ethnic Disparities Among Low-Income Families. PsycEXTRA Dataset. http://doi.org/10.1037/e724082011-001 Townley, A. J. & Schmieder-Ramirez, J. H.,. (2005). School finance: a California perspective. Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt Pub. Co. |

@npriesterEvidence of my learning from SDSU EDL 600 Principles of Educational Administration Archives

August 2015

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed