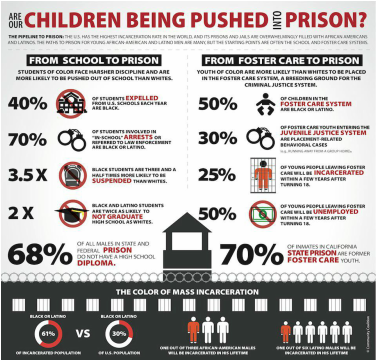

Children Being Pushed into Prison from the Community Coalition Children Being Pushed into Prison from the Community Coalition “Come at me, bro!’ I teased while helping a freshman boy a few months ago. Albert and I giggled as we discussed the dialogue in the narrative he was writing. The classroom was calm and filled with students writing in nooks or in small groups. It was completely normal day in my English class. But, that sentence. That’s all it took. Suddenly, Albert was towering over my chair yelling, cursing, and threatening me. I felt the angry spit of his words hit my face. I could have responded to Albert by following California’s current laws on student discipline. I could have stood up, placed my hands on my hips, waved a finger in his face, scolded his outburst, threatened suspension, and shouted at him to “Get out of my classroom!” as I pointed toward the door. I could have easily pushed him further into what Kemerer and Sansom (2013) explain is known as a “Big Five” action. But, I did not. Instead, I remained seated, sat still, and calmly said, “I’m sorry. I was joking. Calm down. Take a walk.” Even though Albert did not follow through on the threats he voiced, he violated California Education Code 48900(a)(1) because he “threatened to cause physical injury to another person” (Kermer and Sansom, 2013). He could have been suspended, even if it was his first offense. Education codes, such as this one, do not reflect positive behavior intervention supports and trauma informed care. They do not require teachers to identify traumatized students nor do they hold teachers accountable for triggering students or their role in the escalation of “Big Five” behaviors. Instead, they hold students, like Albert, accountable for knowing and abiding by written schoolwide behavior guidelines--regardless of whether or not they know how to read or demonstrate the desired behaviors. Most current California discipline laws are pushing our most underserved and disadvantaged youth from one learning environment to another until many are eventually driven into detention facilities or just out of school altogether. By the time this happens, many students, including many of my high school students at San Pasqual Academy, a residential high school for foster youth, demonstrate significant gaps in their academic and social emotional skills. Based on my informal conversations, approximately the majority of my students have been suspended and a handful have been expelled. This aligns with the claim from the report “Ready to Succeed” from the Stuart Foundation, which claims California’s “Foster youth are suspended at rates nearly triple to the general population” (2011). Eventually, these students continue down what Amurao explains is known as the “school-to-prison pipeline”: 25% of young people leaving foster care will be incarcerated within a few years of turning eighteen” and “70% of inmates in California state prison are former foster care youth.” Suspension rates are not the only contributing factor in the prison pipeline--race, poverty, and adverse childhood experiences--all fuel the drive. But, educators can control the suspensions. Fortunately, a California has passed an assembly bill to address the suspension rates. The report “State Schools Chief Tom Torlakson Reports Significant Drops in Suspensions and Expulsions for Second Year in a Row” from the California Department of Education (2015) explains, “Willful defiance became identified with the problem of high rates of expulsions and suspensions after the CDE reported a high number of minority students were suspended for this cause. Those figures helped spur the passage of Assembly Bill 420, supported by the CDE and sponsored by former Assembly member Roger Dickinson. The bill, signed into law last year, limits suspensions and expulsions for disruptive behavior in certain grades.” As California schools work toward meeting the goals of AB 420, they are implementing systems such as positive behavior intervention supports (PBIS) and restorative justice practices. My district is using local control funding formula (LCFF) to decrease suspension rates. Goal One Action D of the San Diego County Office of Education LCFF aims to “Continue to provide and monitor initial implementation of professional learning for staff on PBIS, trauma informed care and Restorative Justice” (SDCOE). My site was an early adopter of PBIS and is currently working with a coach to integrate restorative justice practices into our interventions. Instead of simply following California law on student discipline, we focus on teaching our students how to behave. In order for this to succeed, teachers and students need to work together to learn how to create a positive learning community. Back to Albert towering over me. Within a few seconds, he simply walked out of the room. I thanked his classmates for remaining calm and listened as they informally debriefed. Within a few seconds, the classroom was again peaceful and productive. I called the school office to notify the staff that Albert had left on a stress walk; he was already in the office debriefing (and crying) with a residential staff member. Albert was not suspended. After school that day, he politely asked to speak with me in private; he offered a sincere apology and admitted that he could not even remember what happened. I accepted his apology, praised him for walking out, and thanked him for coming back to apologize. I also encouraged him to continue working with adults to identify his triggers and manage his responses. He agreed and has since demonstrated significant growth. Just today, Albert sat next to me in class and giggled with me as I helped him edit a project about his future career in law enforcement. Teaching students how to behave will keep students, like Albert, out of the school-to-prison pipeline. Works Cited Amurao, C. (2011). Fact Sheet: How Bad Is the School-to-Prison Pipeline? Retrieved July 18, 2015, from http://www.pbs.org/wnet/tavissmiley/tsr/education-under-arrest/school-to-prison-pipeline-fact-sheet/ Kemerer, F., &; Sansom, P. (2013). California School Law Third Edition. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press. Ready to Succeed. (2011). Retrieved July 18, 2015, from http://www.stuartfoundation.org/OurStrategy/vulnerableYouthInChildWelfare/Initiatives/ReadyToSucceed SDCOE's Local Control and Accountability Plan. (2015). Retrieved July 18, 2015, from http://www.sdcoe.net/about-sdcoe/Pages/Local-Control-Accountability-Plan.aspx Suspension and Expulsion Rates for '13-14 - Year 2015 (CA Dept of Education). (2015, January 14). Retrieved July 18, 2015.

0 Comments

|

@npriesterEvidence of my learning from SDSU EDL 600 Principles of Educational Administration Archives

August 2015

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed