|

Over the past few years, I have inconsistently shared the work occurring in my classroom. Years ago, daily posts on my now-abandoned classroom blog, reflections on my professional blog, and posts on my students’ blogs kept invested adults current about the learning taking place in my classroom. For the past few years, I have practically gone into hiding after moving my classroom from the blogs to Edmodo and then Haiku. I have allowed ambiguous student privacy expectations of my district and partner agencies to discourage me from posting learning to an authentic global audience. Before reading Show Your Work by Austin Kleon, I was only sharing my work through Instagram and practically stopped encouraging my students to share their work.

I am still a little apprehensive about pushing my students to share their work with authentic audiences. When I read about teachers seamlessly integrating social media into their classrooms as a way to have students provide evidence of understanding as in #InstagramELE Challenge by Pilar Munday and using it to support bonding over shared face-to-face experiences as in Instagram Scavenger Hunt by Caitlin Tucker, I felt a little envious. Part of me wants to just grab these engaging activities and incorporate them into my classroom. But then, the reality sinks in. Less than half of my students have smart phones with data plans; of these, many are older devices with limited storage and low resolution cameras. Currently, students are unable to connect personal devices to the student wifi and the guest wifi is turned off during school hours. The residential agency does not provide students with wifi access. Additionally, my partner agencies have contradictory and unrealistic expectations of students’ social media use. Currently, I encourage my students to photograph and post highlights from shared learning experiences, such as field trips, guest speakers, and hands-on activities, but I do not directly integrate the use of social media into the curriculum as Monday and Tucker model. Reading Show Your Work inspired me to return to publicly sharing the work taking place in my classroom. Since reading his book, I have created a classroom website titled Ms. Priester’s Classes. Even though it is not perfect and finished, I have published it. My students have already begun written posts documenting lessons and sharing reflections and work, such as this post “Sketchnoting by Diana and Imani.” I am piloting this in my intersession courses, but my goal is to have a student write at least one post for each course during the traditional school year. I can enhance this by adding a teacher’s toolbox to each posts containing links to copyable versions resources. As I look toward the upcoming school year, I hope to show the work of my students and myself by:

-Reflection of experience -Student work -Student author profile -Teacher resources

Last year, I established classroom goals at the beginning of the year: increase rigorous academic talk, support claims with evidence, and read and comprehend expository texts. This fall, I am considering adding “show your work” to our annual goals.

1 Comment

Edtech leaders who are at the peak of their careers are prolific on social media. These leaders are followed by thousands of educators. They share stories of how they worked hard to achieve success through keynote speeches and recorded talks. Their tip tidbits and tiny insights zip around multiple Twitter though multiple hashtag circles. They seem to have it all figured out. Followers applaud their success through likes and retweets and send messages to seek their opinions and answers to problems. Of course, the accomplishments of these educators deserves celebration and the sharing their learning benefits many teachers and students. However, there is a danger to this “single story.”

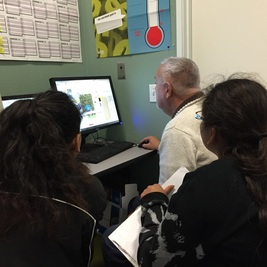

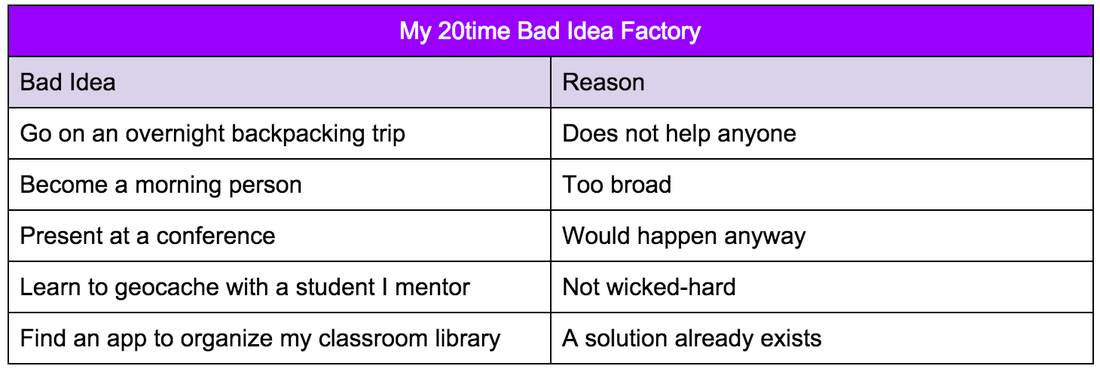

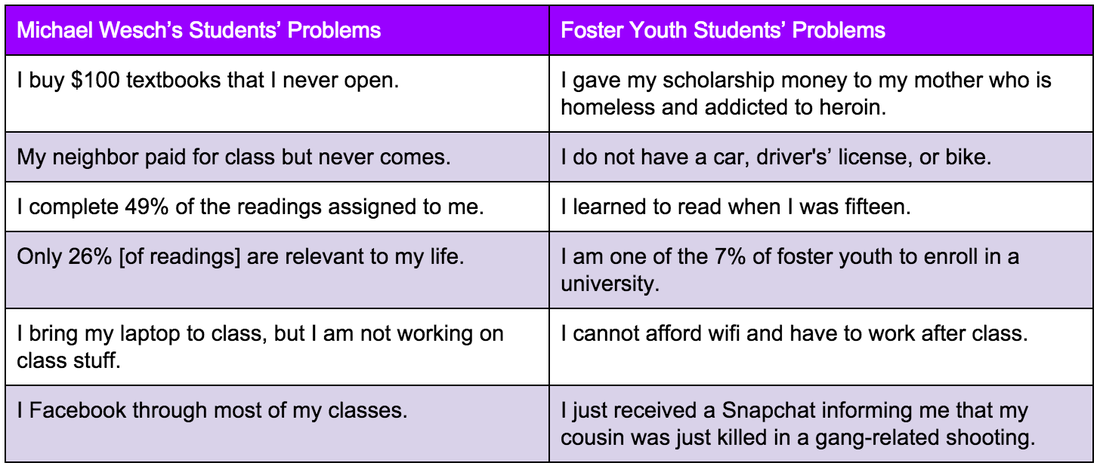

These trending teachers--Wait, no.--These trending educators set an unrealistic expectation for teachers who are just beginning to experiment with using technology in their classrooms. There is a strong focus on sharing today’s best tools and best pedagogy. Only hearing stories of success is overwhelming and intimidating. Where are the stories of the schools who still share computer labs? What about the districts without Google Apps for Education? What about teachers whose administrators do not support technology? What about the students whose parents will not sign release forms? These stories are not heard. Instead, a single story emerging in the edtech community is a fairy tale--currently complete with a pretty blonde princess. Even though current trends and social norms make it challenging to implement, the edtech community should taken into account the warnings Chimamanda Ngozi gives in her TED Talk, “The Danger of Telling a Single Story.” As Ngozi explains, “When we reject the single story, when we realize that there is never a single story about any place, we regain a kind of paradise." Instead of believing yet another fairy tale, we should be working toward creating a diverse, lively paradise filled with the stories of educators at varying levels of edtech integration. Fortunately, my current assignments are pushing my cohort mates and I to tell our stories. But, before I created the Storify of my tweets for the #edl680ig project, I did not even realize I was telling a story. I knew that I was sharing the learning taking place in my classroom--both mine and my students’. As I began to piece my Instagram photos together, I noticed that I was telling a story. I am telling the story of a teacher who is trying to implement current trends and novel ideas into my teaching, but I am also a student with hobbies that balance my academic activities. I am not a rockstar, ninja, or pirate--nor am I seeking to be. I just want to be a good teacher. I know that by following the learning of others, sharing my learning, and taking advantage of opportunities to learn with other educators, I am becoming a better teacher. The single-story that is widely followed by educators on Twitter is a story that leads to notoriety, influence, and personal financial gain--not to the classroom. Sharing the stories of classroom teachers who are still learning provides a collective learning environment--instead of one in which the learners follow an expert. I first saw the RSA Animation of Sir Ken Robinson’s “Changing Education Paradigms” a few years ago. The image of students being pushed through schools on a conveyor belt resonated with me. In response, I have spent years challenging myself to create a learning environment that does more than just move my students along an industrialized system. However, upon watching this video again, I now see that the belief systems behind the current educational paradigms presented in Robinson’s talk clearly relate to my entire campus. At San Pasqual Academy, our classrooms are filled with products/students that should be headed to the outlet mall by this point in production. Most students enroll in our school with missing parts (significant gaps in their academic skills) and extra parts (traumatic experiences). However, we quickly toss them right back onto the conveyor belt--regardless of their abilities or even transcripts--and put them in grade level classes based on their age. We quickly help move them along through our factory to fill in missing graduation requirement courses and even add in A-G requirements. Along the way, we are attempting to fill in the missing parts just enough to get them through and teach them to cover up the extra parts so that they do not slow down the process. It works. Our alumni go to college. Special college admissions criteria for foster youth, financial aid, and well-written personal statements highlighting resiliency and motivation lead to acceptance letters. Multiple scholarships are awarded to every single student on stage during our elaborate graduation ceremony. The adults applaud and clap--congratulating the youth and ourselves for moving another batch of students with missing and extra parts out of the factory. Though we are all well-intending it seems that the invested adults on my campus view people in the popular way Robinson identifies: academic and non-academic. We want our students to be successful, so we push them to become academic adults. The students internalize our beliefs and see college as their only route to success. How could they think otherwise? Almost every single teacher, houseparent, clinician, social worker, judge, lawyer, educational rights holder, mentor, court appointed student advocate, coach, and staff send the message that college should be their goal and that it can provide a path out of the poverty levels and abuse cycles they were born into. Even if we don’t say it, the scholarships bestowed upon them at graduation show it. It’s not working. Robinson is right. The world has changed. The industrialized factory model of education is ineffective. College is not a ticket to success. However, our residential campus is refusing to accept it. This year, we celebrated three recent college graduates during our commencement ceremony. Yes, we are challenging national statistics for foster youth, but we are also contributing to them. Many more of our alumni are unemployed, on public assistance, homeless, incarcerated, or dead. In order to sincerely prepare our students for life after graduation and emancipation, our innovative “first-in-the-nation residential facility for foster youth” needs to challenge the education paradigm that exists on our campus. We are a small, but we have many resourceful, passionate, and creative adults. We have the potential to create a learning environment that teaches students in a way that prepares them for the world they are entering into instead of preparing them for a world that no longer exists. We just need to figure out how. Works Cited Robinsion, K. (2010, October 14). RSA Animate - Changing Education Paradigms. Retrieved July 25, 2015.  Silent Conversation using a Chromebook Silent Conversation using a Chromebook Even though technology is not mentioned in the blog post “A veteran teacher turned coach shadows 2 student for 2 days -- a sobering lesson learned” posted by Grant Wiggins, I have found that integrating technology into the classroom has the potential to actually deepen the “mistakes” noted by the anonymous classroom coach who spent two days shadowing a high school student. In the coach’s experience, “High school students are sitting passively and listening during approximately 90% of their classes” (Wiggins 2014). As a result of years of teaching with one-to-one laptops and Chromebooks at San Pasqual Academy, I have become very skilled at designing lessons to prevent my students from “sitting passively and listening.” My students are always doing something--such as revising a play, working on a group media project, or annotating an article. I am proud of my ability to harness online collaboration tools to support communication, but recently realized that simply helping my students actively engage and decreasing my talking time was not enough. Last year my school’s new instructional coach, Tracey Makings (@MakingsTracey), shared her insight after multiple observations of my classroom: my students were not talking. They were writing, reading, and creating, but they were not being given opportunities to practice and develop the skill of codeswitching into academic talk. And, our daily think-pair-share based on a news article only provided approximately two minutes of talk time for each student. Following my coach’s advice, I went into this year with a goal of helping my students engage in rigorous academic talk. In order to accomplish this classroom goal, I intentionally scheduled opportunities for face-to-face conversations, collaboration, and presentations. And, I had to put the Chromebooks away. I continued take advantage of my learning space; I pushed the students into groups for discussions sitting and standing around our tall triangular desks arranged into squares of four while allowing others to cluster up using chairs and stools from our classroom lounge. I broke my paperless rule and wrote conversation starters on poster papers and/or printed them. Just doing this was a challenge. I have been paperless for so long that it was my routine to create written instructions for every single little lesson, including instructions of how to submit evidence for credit. I felt the need to type questions, write discussion directions, and have at least one student record their group’s responses. I felt like I had to have proof of their learning. But, as they began talking, I noticed that they ignored my printed instructions and only used the prompts. I slowly began to let it go and trusted myself to just listen, observe, and naturally join into conversations as needed. I learned to place one of my additional adults in groups that needed a little direct guidance and allowed more independent groups to form and even stray from the planned topics. During my current unit, I was finally able to completely unplug and allow natural academic conversations to occur. My freshmen just finished reading and discussing the novel Orphan Train by Christina Baker Kline. Throughout the unit, I read aloud to them, they placed sticky notes on sections of the text relevant to our essential question, and we discussed their selections. This evolved into discussion days with specific learning targets, such as asking follow-up questions, with time for everyone to practice a new skill as we talked about the text. During our last few days of reading the book, the students began naturally interrupting me with small verbal responses such as gasps and excited blurts. I could hear the murmur and sense their subtle movements as I read words that evoked emotions and thinking. I would pause. We would quickly have a whole-group conversation about the text and then return to reading and searching for relevant text excerpts. All of this was unplugged-the Chromebooks were neatly stored in the cart for the entire period. I even just used a pencil checkmark on my roster to note which students participated. If I had allowed myself to instead revert to sending the students off to have conversations using a discussion board or even just having the them read online while adding highlights and comments, we would have lost the moments of discussions sparked by shared emotional responses. Unlike instructional coach in Wiggins’s blog post who wishes she “could go back and change [her] classes now,” I am currently changing my classes. As many teachers work to integrate technology into their lessons, I am working to find a balance between screen time and face time. Works Cited Wiggins, G. (Ed.). (2014, October 10). A veteran teacher turned coach shadows 2 students for 2 days - a sobering lesson learned. Retrieved June 20, 2015.  My Yearbook Students Receiving a Lesson from Our Representative My Yearbook Students Receiving a Lesson from Our Representative I would like to say that integration of technology and project based learning is helping to prepare my students to work at Google. But, in reality, my yearbook class is actually doing a better job than my English class. According to Thomas L. Freeman in “How to Get a Job at Google,” the five hiring attributes at Google are: cognitive ability, emergent leadership, humility, ownership, and expertise (2014). The students on my yearbook staff develop these skills as they work together to publish San Pasqual Academy’s yearbook. Cognitive Ability In order to create the yearbook, my students must explore and learn. Their cognitive abilities are tested throughout the design process. The class uses uses a program called StudioWorks to build our book. It is published by our supplier, Balfour, and is completely web-based. The interface is different from almost anything my students have worked with and a simple mistake of pushing a key command that works in another application may cause unsaved work to disappear. Since this program is Balfour’s product, very little just-in-time support exists. We are provided with guidebooks, a representative, and a technical support help desk phone number, but we cannot simply Google a YouTube tutorial when we are stuck. Additionally, yearbook staff is normally very small--only three to five students--and our master schedule often creates years when it is impossible to have any returning students in the class. Instead of walking them through each step of design and publishing, I push them to use their resources to figure things out, provide help when they are stuck, and encourage them to call the help desk phone number when we are all confused. As a result of these challenges, my students often spend hours teaching themselves. Emergent Leadership This spring break, my class faced an unplanned obstacle that escalated one of my students into an unofficial leadership position. My editor faced some personal challenges and had to step back from the project. To fill her place, the photo editor quickly took over. She taught herself to design pages and began delegating the photographic tasks to other students. When the editor returned, they combined skills and increased productivity. This simple challenge provided an opportunity for a student to display and practice emergent leadership skills. Humility In the revision process of creating the yearbook, I often come across a page that does not align with our design theme or contains a stylistic flaw, such as a photo of a person who appears on two consecutive pages. Situations like these create moments when honest, constructive criticism is necessary. In years past, I have had students completely shut down when I told them a page they had worked on needed to be redone or revised. However, when students are able to work through these setbacks, they are able to understand that humility is necessary to collaborate to accomplish a common goal. Ownership This year, ownership has been one of the biggest lessons my yearbook team has learned. In years past, I have swooped in and finished pages after deadlines were missed. The book was completed on time, but the students were not invested in the creation process or deeply proud of the end product. I realized that I had been taking away their ownership. This fall, I told my students that I would not finish the book for them. They did not believe me, because they know that I always swoop in and save them. Unfortunately, my girls are currently in the process of really learning the responsibility of taking ownership. We have already significantly missed our final deadline. But, I am letting them struggle. Instead of just dropping their grades and finishing it on my weekends, they are spending their weekends finishing the book. When the book is printed, it will be their book. Expertise Last year, my yearbook editor was a returning student to the class. Out of all of the students, he was our expert. However, he was not motivated to create the book and resisted teaching other students what he knew. As a result, he actually became more of a hindrance to the creation of the book--even though he knew more than anyone else! We saw that expertise is only useful when the expert is willing and able to contribute to a goal. Looking Ahead Even when I am just teaching an elective class, it is challenging for me to help my students develop the traits necessary to work somewhere like Google. I want to break things down into baby steps and micromanage their projects. I want to make sure they succeed, but I need to give them space to learn. As I look toward the upcoming school year, I want to push myself to create authentic learning experiences in my English classes. As I do so, I need to keep the following in mind:

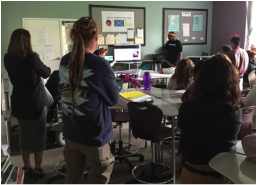

Works Cited Friedman, T. (2014, February 22). How to Get a Job at Google. Retrieved June 21, 2015. Good Ideas Next, I began to consider real problems I do not know how to solve. I also began focusing on my school, because I know that I will be more likely to challenge myself if my students will benefit from my efforts. Instead of focusing on what the end-product will look like, considered the problem--if I knew what the solution would look like, it would not be a “wicked problem.” I came up with the following two ideas, which focus on using technology to help San Pasqual Academy’s (SPA) invested adults to increase our abilities to support our students. By the way, SPA’s strong team of invested adults include: San Diego County Office of Education Juvenile Court and Community school staff, New Alternatives residential staff, YES Program work readiness staff, San Diego County Health and Human Services Agency social workers, Voices for Children Court Appointed Student Advocates, San Pasqual Academy Neighbor grandparents, and miscellaneous educational rights holders. Idea A - Adult Communication Wicked Question How can technology help San Pasqual Academy’s invested adults communicate with one another? Current Problem We have more than 200 adults working together to support 85 students. We work for different agencies, work in different buildings, and work different shifts. Many of us do not even know each other’s names and are unable to identify which adults are connected to individual students. Inquiry Questions

Wicked Question How can San Pasqual Academy’s invested adults increase their familiarity with the social media platforms used by our students in order to support responsible practices? Current Problem We have had problems with conflicts connected to social media disrupting school and residential time. Our campus director recently told me that the majority of the student conflicts addressed by her and her staff involve social media. Many of the adults do not use or understand the platforms used by the students and struggle to teach and/or model responsible practices. Inquiry Questions

Brookhouser, K. (2015). The 20time project: How educators can launch Google's formula for future-ready innovation. San Bernardino, California: 20time.org.  JCCS, New Alternatives staff, and SPA alumni at dinner after a SPA basketball game JCCS, New Alternatives staff, and SPA alumni at dinner after a SPA basketball game Initial Thoughts When I first began thinking about starting a 20time project, I was frustrated. I already enjoy making goals for myself and pushing myself to learn new things. Over the past few years, I have intentionally learned new hobbies and increased my practice of ones I had abandoned, including running, cooking, swimming, hiking, and most recently yoga. I am reading more, using Instagram to regularly share the work being done in my classroom, calling friends regularly, listening to podcasts and audiobooks, and even walking my dogs more. At first, I thought the 20time project was going to require me to integrate another passion into my jam-packed schedule. However after reading The 20time Project: How educators can launch Google’s formula for future-ready innovation by Kevin Brookhouser, M.Ed., I realized that 20time projects more than simply “passion projects.” Brookhouser (2015) explains, “The goal is not to give students school time and resources to play with a ‘passion project.’ It’s not even about the positive community impact their projects might have. It’s about developing the creative abilities needed to tackle wicked problems.” I decided to challenge myself to experience the 20time process while addressing an unsolved “wicked problem” on my campus. Bad Ideas First, I created a Bad Idea Factory brainstorm. Using this tool, it was easy to purge ideas from my list that were simply passion projects, easily solvable problems, unfocused ideas, and outcomes that would not help anyone else. Beginning Blogging When I was hired at San Pasqual Academy in 2006, the school was already blogging. I was expected to join my new colleagues by creating a blog using Blogger and to post homework assignments before leaving work each day. Sometime around 2009, I began having my students blog. I regret to say that I am unsure of the timeline because I actually deleted the first few years of my blog posts while I was pursuing my first MA because I was embarrassed of their outdated methods and content. Anyway, each student had a Blogger account and regularly posted their writing. I linked all of their blogs to my blog so we could share comments. The blogs were public. I shared URLs the students’ invested adults and taught them how to comment during conferences. Once we began receiving comments from strangers, we became excited. We added widgets that mapped the location of our visitors using little red dots. Eventually, we added labels--a predecessor to the hashtag--and used Google Reader to aggregate our feeds. The students used images, embed codes, and links to enhance their posts. As we began using Google Docs (now known as Google Drive) and Web 2.0 tools, they also embedded these into their feeds. I knew I was giving my students and authentic global audience, raising the stakes of their work, supporting collaboration, providing transparency, and increasing their technology skills while helping them build positive online reputations. This was more than five years ago. I was was one the early adopters. I believed in the work I was doing. But, I stopped. Changes Three years ago, my district, San Diego County Office of Education’s Juvenile Court and Community Schools, experienced changes in leadership. Under the previous administration, I had been encouraged to be innovative and was supported through obstacles. But, the technology coordinator was transferred to another department and the executive director and my principal were released. The new administrators, and administrators from the county office, began to express concern about potential problems that may arise from allowing students to produce public work using their own accounts using district devices and internet connection. I suddenly began to see potential mistakes as liabilities. Additionally around that time, my campus experienced a challenge in student privacy when the local newspaper asked to write an article about our football team but instead revealed information about a player’s father who had been involved in a major local news story. Our doors to global audiences began to close. Our “first-in-the-nation” residential academy that had aired graduation ceremonies on local television stations and been featured in numerous television shows and magazines, including the Today Show and Sports Illustrated, began to be more concerned with privacy than building our reputation. I was afraid the students’ lawyers and educational rights holders would not understand the benefits of their youths’ blogs. Instead of attempting to speak up, persuade them, or even create a compromise, I just moved away from the blogs. Also, I no longer needed my classroom blog to post assignments because I was using Edmodo, which created a Facebook-like assignment feed and gradebook. Currently, I use Haiku learning management system. My old classroom blog has not been updated since February of 2013. To address the safety risks, my district began using Google Apps for Education (GAFE) three years ago. Our technology resource teacher, Jeff Heil (@jheil65), encouraged and supported me as I guided my students in transitioning from their personal Google accounts to monitored GAFE accounts. My current juniors were the last class to create public blogs. Present Status Currently, my students have blogs, but we do not really use them. I do not even have a complete aggregated list of their links. We do not use the comment features. We still share our work publicly by posting it to their personal social media, but we do not intentionally write for a public audience. I know that I need to re-establish the practice of blogging in my English 9 and 10 classes. The student voices in “Transforming Teaching and Learning with an Authentic Audience” from Jeff Jakob (2013), remind me of why I need to find a way to reintegrate public blogging into my curriculum. As Grant Wiggins stated in the Jakob (2013) video, “Students work harder with a much greater focus on what they are trying to accomplish when there is a real and virtual audience they have to deal with.” I believe this. I have already experienced it. Now, I just need to have the courage to take risks by using blogging again. Blogs are a simple way to create opportunities for my students to connect with a global audience. Blog Archives I am forcing myself to share these blogs. I feel like I am sharing a draft version of a writing process and like I need to justify them. I will keep it simple. They are from years ago and I was still learning. They are not perfect. There are years of growth that has occurred since I left these behind, but that is for another time. Reference

Jakob, J. (2013, June 6). Transforming Teaching and Learning with an Authentic Audience. Retrieved June 15, 2015.

Last fall, I took a group of my sophomores to Fiesta Island for a bonfire as part of a storytelling unit. After the live storytelling concluded, we relaxed, chatted in small groups, and ate s’mores. After awhile, I noticed two of my girls had their cell phones out. My first reaction was frustration We were off campus having an authentic experience and they were on their phones! But, instead of snapping at them, I just observed. One was filming the other as she talked about her s’more. I inquired. They showed me a Snapchat story documenting the entire night. They were not avoiding the experience, they were actually documenting and sharing the highlights. They were still storytelling--just not the type I has pictured when I planned a night around a campfire.

Currently, I am a daily Snapchat user. I eagerly share my Snapchat excitement with other adults and have facilitated many tutorials filled with giggles and silly faces. Like most new social media tools, Snapchat is easier to just try than to try to explain. Snapchat feels natural because the messages are meant to be quick and temporary--just like face-to-face communication. However, the the back and forth sharing of photos and videos layered with drawings and text is a novel way to communicate. Snapchat is not just about sexting or selfies--it is a disruptive literacy. As Casey Neistat’s (2014) explains Snapchat is “about giving people an easy way to tell a story.” In his video “Snapchat Murders Facebook” he explains that Snapchat stories are different because they are disappear after twenty-four hours to create a sense of urgency and provide an authentic timeline (2014). However, he does not elaborate on how Snapchat creating a new form of communication that blends together images, text, drawing, and videos. As an English 9 and 10 teacher, it is my responsibility to help my students become literate young adults. Snapchat is another reminder that literacy now extends beyond simple reading and writing. I have not yet directly integrated Snapchat into a lesson (it was offered as an option on one project, but no one used it). However, I encourage my students to use it in class to record and share fun and interesting moments. I also model this by adding the moments to my own Snapchat story. Reference Neistat, C. (2014, October 2). Snapchat Murders Facebook. Retrieved June 14, 2015.  Project presentations in my classroom with "experts" and campus adults in the audience PC: Natalie Priester Project presentations in my classroom with "experts" and campus adults in the audience PC: Natalie Priester The purple and teal walls of my high school classroom look quite different from the bland ones of Michael Wesch’s university classroom. But, if they could talk, they would point out the differences in our student populations and the differences in our students’ skin color--but that is another conversation. His students’ complaints address valid concerns about our current education system and he explains how technology is changing teaching and learning. The ideas shared in Wesch’s 2010 video, “From Knowledgeable to Knowledge-able,” have been developed among the edtech community over the past five years; “embrace real problems, let students collaborate, and harness relevant tools.” Currently, I am confident in my ability to create lessons that push students to collaborate and use tools, but I am still working on figuring out the best type of “real world problems” to ask my students to explore. When developing project-based learning units or even just selecting text for my English 9 and 10 classes, I often get hung up on Welsh’s question, “What do we need to know for the rest of our lives?” I know my freshmen and sophomores should publish “something of worth” to keep up with the privileged students from our county’s High Tech High and Canyon Crest Academy who will be sitting next to them in college classes in a few years. However, I also acknowledge my students’ pasts, current challenges, and harsh realities they will face after graduation--just this morning I found out that one of our alumni just died of an overdose. Wesch’s 2010 statement that students should be taught to “embrace real problems” is a predecessor to the current trend of problem-based learning, which I am currently attempting to implement in my classroom. This past spring, I created a unit following the Buck Institute’s Project Planner. As I developed the unit, I intentionally decided to select a driving question directly relevant to my students. I want to help them learn this new learning process before pushing them into advanced unfamiliar content. My sophomores answered the question “How can we use digital media to persuade foster youth to attend San Pasqual Academy?”. While working on the project, students followed Wesch’s steps to “connect, organize, share, collect, collaborate, and publish.” I stepped back, observed, and coached as they worked. I learned that the learning which occurred throughout the entire process--from brainstorming to debriefing after the showcase--and was greater than the content of the videos they produced. In the effort of pushing myself to share, my Resident Recruitment project plan is available here. Looking ahead to the units I will plan for this summer and the upcoming school year, I want to continue to create problem-based learning units. But, I am not going to jump my freshmen right into trying to solve the world’s problems. Instead, I want them to focus on learning the process. I want the content they explore to be “of worth” to their lives, such as independent living skills, managing emotions, social skills, financial literacy, and creating and maintaining healthy relationships. These baby steps will help them to slowly build toward what Wesch terms as “knowledge-able.” Ideally, these units will better prepare them to emancipate from the foster care system while also preparing them to participate in college classes with those High Tech High students. Resource TEDxKC - Michael Wesch - From Knowledgeable to Knowledge-Able. Retrieved June 9, 2015, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=leaahv4uti8 |

@npriesterA collection of my learning from SDSU EDL 680 Seminar in Personalized Learning Archives

August 2015

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed