|

Carol Dweck’s book Mindset: The New Psychology of Success asserts that humans have two mindsets: a fixed mindset is the belief that traits, such as intelligence and personality, are permanent and the growth mindset is the belief that traits can be developed. Dweck supports this claim by sharing her research, personal reflections, celebrity examples, and various anecdotes in the contexts of athletics, business/leadership, relationships, and parenting/teaching/coaching. Dweck’s purpose is to enable readers to understand the two mindsets in order to develop growth mindsets. Writing in an informal tone that explains psychology using simple vocabulary, supported by examples from clients to working professionals to pop culture icons, Dweck writes to a contemporary adult audience with little experience in the field of cognitive psychology.

Even though Dweck does not specifically discuss educational technology, Mindset has already positively affected my work. As explained in my previous posts, I was able to calmly learn from a failure by applying a growth mindset, I can identify mindsets in my students, and I feel prepared to share Dweck’s work with my students and campus adults. It seems that individuals with growth mindsets are better prepared to learn new technology and continue to learn as pedagogy and content change in response to technology. By helping my students, colleagues, and campus adults develop growth mindsets, I will empower them to be receptive to change and motivated to learn. To expand upon Dweck’s recommendation to teach others about mindsets and use feedback to encourage growth mindsets, I will follow and engage in the ongoing mindset conversation in social media. I am looking forward to learning more about how to respond to fixed mindsets and how to nurture growth mindsets.

1 Comment

Over the past few years, I have inconsistently shared the work occurring in my classroom. Years ago, daily posts on my now-abandoned classroom blog, reflections on my professional blog, and posts on my students’ blogs kept invested adults current about the learning taking place in my classroom. For the past few years, I have practically gone into hiding after moving my classroom from the blogs to Edmodo and then Haiku. I have allowed ambiguous student privacy expectations of my district and partner agencies to discourage me from posting learning to an authentic global audience. Before reading Show Your Work by Austin Kleon, I was only sharing my work through Instagram and practically stopped encouraging my students to share their work.

I am still a little apprehensive about pushing my students to share their work with authentic audiences. When I read about teachers seamlessly integrating social media into their classrooms as a way to have students provide evidence of understanding as in #InstagramELE Challenge by Pilar Munday and using it to support bonding over shared face-to-face experiences as in Instagram Scavenger Hunt by Caitlin Tucker, I felt a little envious. Part of me wants to just grab these engaging activities and incorporate them into my classroom. But then, the reality sinks in. Less than half of my students have smart phones with data plans; of these, many are older devices with limited storage and low resolution cameras. Currently, students are unable to connect personal devices to the student wifi and the guest wifi is turned off during school hours. The residential agency does not provide students with wifi access. Additionally, my partner agencies have contradictory and unrealistic expectations of students’ social media use. Currently, I encourage my students to photograph and post highlights from shared learning experiences, such as field trips, guest speakers, and hands-on activities, but I do not directly integrate the use of social media into the curriculum as Monday and Tucker model. Reading Show Your Work inspired me to return to publicly sharing the work taking place in my classroom. Since reading his book, I have created a classroom website titled Ms. Priester’s Classes. Even though it is not perfect and finished, I have published it. My students have already begun written posts documenting lessons and sharing reflections and work, such as this post “Sketchnoting by Diana and Imani.” I am piloting this in my intersession courses, but my goal is to have a student write at least one post for each course during the traditional school year. I can enhance this by adding a teacher’s toolbox to each posts containing links to copyable versions resources. As I look toward the upcoming school year, I hope to show the work of my students and myself by:

-Reflection of experience -Student work -Student author profile -Teacher resources

Last year, I established classroom goals at the beginning of the year: increase rigorous academic talk, support claims with evidence, and read and comprehend expository texts. This fall, I am considering adding “show your work” to our annual goals.

Edtech leaders who are at the peak of their careers are prolific on social media. These leaders are followed by thousands of educators. They share stories of how they worked hard to achieve success through keynote speeches and recorded talks. Their tip tidbits and tiny insights zip around multiple Twitter though multiple hashtag circles. They seem to have it all figured out. Followers applaud their success through likes and retweets and send messages to seek their opinions and answers to problems. Of course, the accomplishments of these educators deserves celebration and the sharing their learning benefits many teachers and students. However, there is a danger to this “single story.”

These trending teachers--Wait, no.--These trending educators set an unrealistic expectation for teachers who are just beginning to experiment with using technology in their classrooms. There is a strong focus on sharing today’s best tools and best pedagogy. Only hearing stories of success is overwhelming and intimidating. Where are the stories of the schools who still share computer labs? What about the districts without Google Apps for Education? What about teachers whose administrators do not support technology? What about the students whose parents will not sign release forms? These stories are not heard. Instead, a single story emerging in the edtech community is a fairy tale--currently complete with a pretty blonde princess. Even though current trends and social norms make it challenging to implement, the edtech community should taken into account the warnings Chimamanda Ngozi gives in her TED Talk, “The Danger of Telling a Single Story.” As Ngozi explains, “When we reject the single story, when we realize that there is never a single story about any place, we regain a kind of paradise." Instead of believing yet another fairy tale, we should be working toward creating a diverse, lively paradise filled with the stories of educators at varying levels of edtech integration. Fortunately, my current assignments are pushing my cohort mates and I to tell our stories. But, before I created the Storify of my tweets for the #edl680ig project, I did not even realize I was telling a story. I knew that I was sharing the learning taking place in my classroom--both mine and my students’. As I began to piece my Instagram photos together, I noticed that I was telling a story. I am telling the story of a teacher who is trying to implement current trends and novel ideas into my teaching, but I am also a student with hobbies that balance my academic activities. I am not a rockstar, ninja, or pirate--nor am I seeking to be. I just want to be a good teacher. I know that by following the learning of others, sharing my learning, and taking advantage of opportunities to learn with other educators, I am becoming a better teacher. The single-story that is widely followed by educators on Twitter is a story that leads to notoriety, influence, and personal financial gain--not to the classroom. Sharing the stories of classroom teachers who are still learning provides a collective learning environment--instead of one in which the learners follow an expert.

The fixed mindset often appears in my classroom, compounded by the fact that many students have significant gaps in their education due to their experiences prior to, and within, the foster care system. Students are often resistant to even try to learn. These students will eagerly will show what they can do but avoid the challenge of learning new skills. The following are examples of how students’ mindsets appear in my classroom.

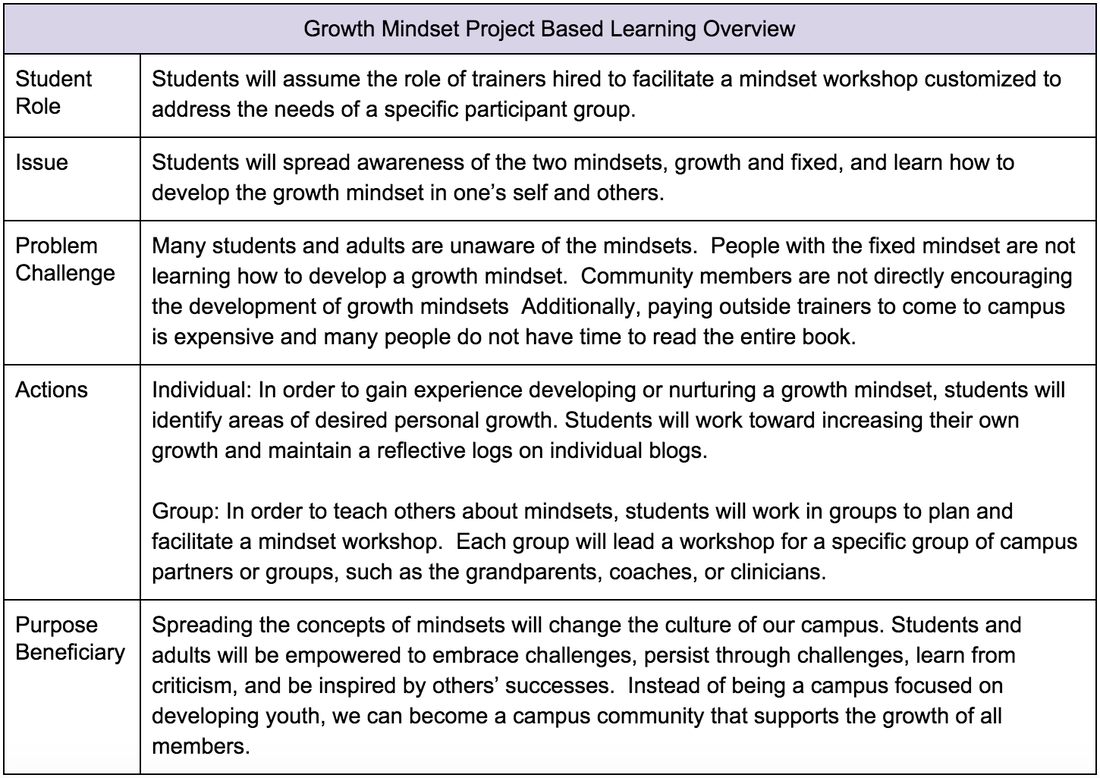

"I don’t!” As a simple assessment of my students’ experience in reading and writing, I often ask new students about their favorite books. I occasionally I hear a simple, “I don’t read.” John was one of these students. But, he did more than just not read--he did not want to do anything in English class. He said he did not “do English” and avoided writing tasks by distracting himself. He refused to read aloud. When pushed, he talked on and on about one novel he read in sixth grade. When given an independent reading assignment, he purchased the same book and asked to re-read it for high school credit. His behaviors clearly stated that he did not want to do the work because he did not know how, but he was unwilling to utilize the resources around him (including upperclassmen tutors and teachers’ assistants who offered to work with him in a private setting). John’s fixed mindset convinced him that he was incapable of learning more. He successfully read that one novel and clings to it. He did not pass my class. Currently, I am attempting a new approach by asking John to read a graphic novel with a teacher’s assistant. Even though, this reading task may provide some success, I can better support John by teaching him about mindsets and creating opportunities for him to grow. “It’s hard!” When Steven entered my class as a freshman, he was barely able to decode words. When reading silently, he was able to comprehend at a fourth-grade reading level, but he would pout or walk out of the room if asked to read aloud. A few weeks into the fall semester, I noticed that Steven would sneak into the back room during silent reading. It seemed as if he was trying to focus, but I soon discovered that he was actually using technology tools to improve his comprehension. He found audio clips of the novel that we were reading on YouTube and he was listening to them as he followed along in his text. In cooperation with the campus literacy coach, his houseparents, and upperclassmen tutors, we were able to provide Steven opportunities to read aloud. By the conclusion of his sophomore year, Steven was independently reading grade-level texts, especially teen romance novels. This spring, he passed the California High School Exit Exam on the first try and earned a 4.0 grade point average. He is open about his progress and loves to tell his peers about his improvement. Stephen’s commitment to working hard to improve his skills exemplifies his growth mindset and is becoming one of the most respected students on our campus. “I won’t even try!” The majority of my freshmen students have very little experience with expository writing--a few even claim to have never written any type of essay. When Manny asked “Do you want me to include the counterclaim in this body paragraph or do you want me to make a new paragraph for it?” I was taken aback. By inquiring about his educational experiences, I learned that he attended a middle school with high expectations. His eighth grade English teacher had emphasized expository writing. I told Manny that I was excited to read his work and challenge him to improve his writing. But, within a few weeks, Manny shut down. He stopped writing. He withdrew from the class. He became defensive when I attempted to help him. I set up a meeting with his clinician after school one day. Manny begrudgingly participated in the meeting, but became visibly upset after I kindly explained, “You are fortunate that you are entering high school with advanced writing skills. Your strong critical thinking skills are evident in your participation in class discussions. The door to college will be open to you. I am looking forward to helping you get there.” Sounds nice, but that conversation led to a six-month shut down. Even after many meetings with campus adults, Manny refused to participate in class. Manny has a fixed mindset and my comments about his innate intelligence and potential put too much pressure on him. When he faced a challenge in class, he stopped trying because it caused him to feel like I had lied--if he was smart he would have been able to accomplish the task without support. Fortunately, semesters end and courses can be retaken. Currently, Manny is beginning to accept support from adults and is pushing himself to earn high grades. However, I need to be mindful of his fixed mindset and praise his growth in skills instead of his talents. Impact Even though many of my students seem to demonstrate fixed mindsets, the adults at San Pasqual Academy can help them to develop growth mindsets. As Dweck explains, “Every word and action can send a message. It tells children— or students, or athletes— how to think about themselves. It can be a fixed-mindset message that says: You have permanent traits and I’m judging them. Or it can be a growth-mindset message that says: You are a developing person and I am interested in your development” (2008). This reinforced the previously mentioned practice shared by experienced campus adults; balance care with challenge. To support the growth mindset, we need to emphasize development. By doing this, we help our students to overcome trauma and the fixed mindsets frequently instilled in them by their previous caregivers. Works Cited Dweck, Carol (2006-02-28). Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. Random House Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.  After just reading the first few chapters of Mindset: The New Psychology of Success by Carol Dweck, I knew that I wanted to at least share the concepts of growth and fixed mindsets with my students. After reading, the chapter “Parents, Teachers, and Coaches: Where to Mindsets Come From?”, I realized that sharing the mindsets with my students would not be enough. If want mindsets to become part of the campus culture of San Pasqual Academy, I need to reach the adults, too. Bad Ideas Over the past few weeks, I have become increasingly aware of the popularity of mindsets among educators. Mindset is a popular hashtag, mindset infographics and articles are commonly tweeted, and many users list the mindset in their Twitter profiles. I have even received direct Twitter messages from a user stating that she is “on a mission to spread the growth mindset.” So, I was not surprised to discover that will minimal search effort, I was able to find an abundance of mindset resources. While collecting resources, I stumbled upon the upcoming conference Academic Mindsets : Promoting Positive Attitudes, Persistence and Performance hosted by Learning and the Brain. However, once I saw the registration price of $499, I scratched it off my list. My district supports professional development, but that seems a little pricey. Additionally, the conference is not until February 2016 and I want to bring mindsets to my school this fall. I also discovered many fee-based resources that support Mindsets, including Mindset Works’ Brainology Program, which costs $6,000 per school site. Again, I moved on. Next, I considered the idea of using the free mindset resources available online to create and facilitate a mindset professional development session for the school staff at my site. When I remembered our already packed professional development agendas, I thought of asking my district and our partner agencies to purchase copies of Mindset: The New Psychology of Success and host book clubs throughout the year. And then I remembered by preexisting list of special projects and decided that it would be unwise to start another project that would take my time away from directly supporting the learning taking place in my own classroom. Wait! Classroom? Project? Oh! I already know the perfect way to integrate the growth mindset into my campus! Rad Ideas Instead of using mindset as an add-on, I decided to directly integrate it into my curriculum. Since my site is switching to block schedules and trimesters this year, I already plan to implement at least one large problem-based learning unit into each course. I am going to use Mindset as one of these large projects; the students will read the book as an anchor text and participate in problem-based learning based on Dwek’s key concepts. Read Mindset Instead of a whole-class novel, I am going to teach a whole-class informational text. I will request a class set of Mindset: The New Psychology of Success from my district. I plan to customize the rhetorical reading and writing strategies utilized in the California State University’s Expository Reading and Writing Curriculum to help my students comprehend and analyze the text. We will focus on key ideas, craft and structure, and writing explanatory texts. Teach Mindset Instead of teaching about mindsets, I am going to have my students develop their own growth mindsets and teach others about mindsets. I will build the project by following the Buck Institute for Education’s Project Based Learning Project Planner template. The following is a summary of the project. Works Cited

Dweck, Carol (2006-02-28). Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. Random House Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.  Chapter 7: Knowing, Making, and Playing Quote “A lifelong ability to learn has given human beings all kinds of evolutionary advantages over other animals...homo sapiens, homo faber, and homo ludens—or humans who know, humans who make (things), and humans who play” By explaining that play has given humans an “evolutionary advantage,” Thomas and Brown validate play as more than meaningless activity done by children and recreational breaks taken by adults. It also leads the reader to believe that play can lead to success. Question “Whatever one accomplishes through play, the activity is never about achieving a particular goal, even if a game has a defined endpoint or end state. It is always about finding the next challenge or becoming more fully immersed in the state of play.” What types of challenges should educators create? Is gamification and badging enough? Connection “In a world where images, text, and meaning can be manipulated for nearly any purpose, an awareness of the play of context and the ability to reshape it become incredibly important parts of decision making.” In my previous MA program, I explored research transliteracy. At the time, the term was being used among librarians and focused on helping students comprehend multiple forms of media, such as videos, websites, and audio files. It was an appropriate issue to discuss at the time, but the term transliteracy has now been replaced with digital literacy. Thomas and Brown extend upon the concept of literacy by explaining that students need to be able to do more than comprehended digital media-they need to be able to communicate using these mediums. Epiphany “Learning content through making is a very different exercise from learning through shaping context.” Making resonates more than shaping content. Consider the questions “What did you make today?” Followed by, “What did you learn while making that?” These are much different than a simple, “What did you learn today?” Chapter 8: Hanging Around, Messing Around, and Geeking Out Quote “Geeking out provides an experiential, embodied sense of learning within a rich social context of peer interaction, feedback, and knowledge construction enabled by a technological infrastructure that promotes “intense, autonomous, interest driven” learning.” When people “geek out,” they become the “lifelong learners” educators have been striving to create for the past few decades. The social connections, tools, and access to information provided by technology enable learners to “geek out.” Question “In essence, hanging out is a social, not merely technological, activity. It is about developing a social identity.” Our students are already building these identities, but so many educators just look the other way. How can create and encourage hanging out experiences for adults? Is Facebook enough? Connection “Experimenting with the familiar in terms of content and tools is apt to open up a gap between this first unfocused form of play and the potential that emerges because of it. The gap is between the way something could be—what a person begins to imagine she can accomplish—and the way it is.” “I have an idea. Hang on.” “What is it?” “It’s a surprise. Let me go try to make it. BRB” This conversation regularly occurs between my cohort mate Jake Bowker (@jbowker88) and I. We often share tools and discuss our learning, but sometimes he just completely disappears to immerse himself in play. He will spend hours teaching himself how to use tools he already knows and/or discovering new tools needed to create his project. Often, his vision of “way something could be” ends up evolving along the way as it is shaped by the learning that occurs as through play. This play leads to an increase his learning and the quality of his product. Epiphany “Ito and her team constructed a typology of practices to describe the way young people participate with new media: hanging out, messing around, and geeking out. We believe that these three practices could frame a progression of learning that is endemic to digital networks.” Okay, Jeff! Of course, as soon I read the title to this chapter, I could hear Jeff Heil’s (@jehil5) proud chuckle. The three badges we are earning in this class are named after these three practices. Additionally prior to any exposure to this text, I already used the term “geeking out” in a way that aligned with this meaning. I often say that I “geek out” when I spend hours on my laptop building an invented project. Lately my “geekiness” has been enhanced as I share and collaborate with my peers. Chapter 9: The New Culture of Learning for a World of Constant Change Quote “And where imaginations play, learning happens.” In preschools, imaginative play is a part of the daily routine and integrated into many lessons. As a result, the young children in these environments spend their days immersed in learning and chose to engage in imaginative play during free time, such as playground time. This applies to the students in our classrooms and people in general. The best way to encourage learning is to provide opportunities for students’ to play. Question “Only when we care about experimentation, play, and questions more than efficiency, outcomes, and answers do we have a space that is truly open to the imagination.” Why do all of the academic examples focus on colleges and universities? Are primary and secondary institutions really that far off? What about schools like High Tech High? Connection “The team relies on everyone to understand that their success as individuals creates something that amounts to more than the sum of its parts.” In my roles as ASB adviser, yearbook adviser, and volleyball coach, I support teams of students as they work together to create or accomplish something that is greater than what any individual student--or I-- could produce. Even with all of this experiences, it is still challenging to provide similar learning opportunities in classroom lessons. Epiphany “Maybe members of the new collective will provide an existing piece of information that makes the problem solvable. Or maybe they will inspire a player to find a new, unique solution to the problem and share it with the collective in turn.” This is why we need more people in the edtech community! Currently many vocal and visible leaders, or “educelebrities,” exist among this group, but many questions and challenges still exist. By bringing new educators into the conversation, we may be able to find “unique solutions” that will benefit all of our students. Works Cited Thomas, D., & Brown, J. (2011). A new culture of learning: Cultivating the imagination for a world of constant change. Lexington, Ky.: [CreateSpace?].  Two weeks ago, I made my first conference presentation. I presented Writing from the Ground Up with Google Drive at the EdTechTeam Google Apps for Education (GAFE) Summit Riverside. When the session began, I was excited. The room was packed with almost fifty eager-to-learn participants. I pushed them to begin with an activity instead of just sitting idly and taking notes. I sensed their reluctance, but they jumped right in and began exploring a shared Google Drive folder containing writing process templates and samples. Then, it all blew up. Suddenly, the template folder was missing and copies of documents began popping up by the dozen. I attempted to just fix the problem by using revision history by identifying the folder thief and restoring the folder. This worked, but as soon as I moved the templates folder back to the shared folder another participant took the resources folder! And copies just kept appearing! It was a mess. I kept my cool. I smiled. I enlisted the support of a colleague who was in the session along with a few of the more experienced participants. But, it was too big of a mess to fix within a few minutes. And, every time I looked up someone was walking out the door! I took a deep breath. I abandoned my hands-on session that followed an inquiry model. I sat on a desk. I thanked the twenty remaining educators for their patience and began telling them how I use Google Drive to support the writing process. I showed examples and student work. A few actually seemed relieved to learn by simply listening and watching instead of creating their own documents. They were friendly and praised the tools and process I shared. I promised to locate the stolen folders and send an email containing new folder and instructions guiding them to make individual copies. I smiled as they left. But, behind the smile, I was frantically thought about how I knew better. I have been using Google Drive since before it was even called Drive. I knew shared folders were messy. I knew I should have used file>make a copy, but instead I decided to try something new in an attempt to have my participants collaborate and share their work. What was I thinking? Also, I hadn’t considered that many GAFE participants are complete beginners--even though I had labeled my session #beginner and #intermediate. I failed. My presentation was a flop. (I was secretly grateful these beginning GAFE users were also not very active on Twitter!) If this presentation had occurred a year and a half ago, it would have devastated me. I may have even begun crying or become visibly frustrated. I may not have been able to salvage the session. Even if I had pulled through, I would have been incredibly embarrassed. My mind and mouth would have been filled with frustrated criticisms and complaints. I would have felt like I was not good enough to present. I would have given up. At that time, I had what Carol Dweck, the author of Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, explains is a fixed mindset; I fell into the practice of “Believing that...qualities are carved in stone” (2008). At the time of the presentation, I was halfway through Dweck’s book, but I had already been unintentionally transitioning from a fixed mindset to a growth mindset for more than a year. The growth mindset, according to Dweck, follows “the belief that your basic qualities are things you can cultivate through your efforts” (2008). I have already had a year and a half of change due to a growth mindset. The growth began with small things like changing my eating habits, domestic routines, and exercise practices and intentionally returning to abandoned hobbies. As I began to have small successes in these areas, my confidence grew. I allowed myself to listen to the part of me that knew I was capable of growth. This led to even larger changes, including decreasing my commitment to extracurricular activities at school, ending a long-term relationship, purging hundreds of items from my home, closing my eBay business, and enrolling in a masters program. Reading Dweck's book has helped me to realize that I have a growth mindset. But, the way I handled this presentation flop showed more than just my willingness to learn. I allowed myself to fail without being hurt. As Dweck explains, “Even in the growth mindset, failure can be a painful experience. But it doesn’t define you. It’s a problem to be faced, dealt with, and learned from” (2008). The pages of Mindset was not my first exposure to the idea that failures create opportunities for learning. One of my close friends, Hunter Gluam (who has never even heard of Mindset) encourages growth mindset thinking. When I discuss a challenging situation or relationship with him, he says, “But, what are you learning from this experience? What is this person teaching you? If it hurts, identify the cause of the pain and be grateful for the pain. How is it changing you?” Without realizing it, Hunter has been encouraging me to seek challenges and take risks. Additionally, I recently read Kevin Brookhouser’s book The 20Time Project: How Educators and Parents Can Launch Google’s Formula for Future-Ready Innovation. Brookhouser encourages teachers to “set your students up to fail” because “Every student is counting on us to teach them failure so they can learn to persist, to get dirty, to take risks, to fail without giving up, to dust themselves off, and to keep making and producing no matter what. Additionally, the idea of providing opportunities for failure in classrooms is currently trending among the edtech community on Twitter. Because I have allowed myself to listen to the voices supporting a growth mindset, I was able to walk out of the session giggling as I sent a selfie to my friends to amuse them with news of my “epic fail.” At lunch, instead of pouting or complaining, I began debriefing the experience with my friends. My colleague, Cheryl Lynch (@clynchjccs), who was also presenting for the first time and I decided that we will need to practice presenting at small conferences before presenting at a larger local conference. We began immediately researching future conferences. My colleague and current professor, Jeff Heil (@jheil65), laughed at the story about my presentation and said, “Didn’t I tell you? Never share a folder. That’s like presenting rule number one. Always use file>make a copy. Next time.” Instead of being mad, I just laughed and harassed him for not telling me sooner. Later, an experienced presenter who I had just met that weekend, Jesse Lubinksy (@jlubinsky), advised, “You just need reps. It takes awhile. I was even nervous today as I began my large session today. Keep presenting.” I did not completely realize that day, but the people I chose to spend my time with also posses the growth mindset; they were able to see my story as a learning experience--not a definition of my ability. As I drove home from the conference, I excitedly decided that I would apply to present at the next available GAFESummit. I knew that preparation and time commitment would add to my busy schedule, but I wanted to push myself to improve. As Dweck states, “People in a growth mindset don’t just seek challenge, they thrive on it” (2008). I agree. My application to the GAFESummit Orange County was accepted. I will present Writing from the Ground Up with Google Drive again. And, this time, I will use file>make a copy. Works Cited Brookhouser, Kevin (2015-01-25). The 20Time Project: How educators and parents can launch Google’s formula for future-ready innovation. Kindle Edition. Dweck, Carol (2006-02-28). Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. Random House Publishing Group. Kindle Edition. I first saw the RSA Animation of Sir Ken Robinson’s “Changing Education Paradigms” a few years ago. The image of students being pushed through schools on a conveyor belt resonated with me. In response, I have spent years challenging myself to create a learning environment that does more than just move my students along an industrialized system. However, upon watching this video again, I now see that the belief systems behind the current educational paradigms presented in Robinson’s talk clearly relate to my entire campus. At San Pasqual Academy, our classrooms are filled with products/students that should be headed to the outlet mall by this point in production. Most students enroll in our school with missing parts (significant gaps in their academic skills) and extra parts (traumatic experiences). However, we quickly toss them right back onto the conveyor belt--regardless of their abilities or even transcripts--and put them in grade level classes based on their age. We quickly help move them along through our factory to fill in missing graduation requirement courses and even add in A-G requirements. Along the way, we are attempting to fill in the missing parts just enough to get them through and teach them to cover up the extra parts so that they do not slow down the process. It works. Our alumni go to college. Special college admissions criteria for foster youth, financial aid, and well-written personal statements highlighting resiliency and motivation lead to acceptance letters. Multiple scholarships are awarded to every single student on stage during our elaborate graduation ceremony. The adults applaud and clap--congratulating the youth and ourselves for moving another batch of students with missing and extra parts out of the factory. Though we are all well-intending it seems that the invested adults on my campus view people in the popular way Robinson identifies: academic and non-academic. We want our students to be successful, so we push them to become academic adults. The students internalize our beliefs and see college as their only route to success. How could they think otherwise? Almost every single teacher, houseparent, clinician, social worker, judge, lawyer, educational rights holder, mentor, court appointed student advocate, coach, and staff send the message that college should be their goal and that it can provide a path out of the poverty levels and abuse cycles they were born into. Even if we don’t say it, the scholarships bestowed upon them at graduation show it. It’s not working. Robinson is right. The world has changed. The industrialized factory model of education is ineffective. College is not a ticket to success. However, our residential campus is refusing to accept it. This year, we celebrated three recent college graduates during our commencement ceremony. Yes, we are challenging national statistics for foster youth, but we are also contributing to them. Many more of our alumni are unemployed, on public assistance, homeless, incarcerated, or dead. In order to sincerely prepare our students for life after graduation and emancipation, our innovative “first-in-the-nation residential facility for foster youth” needs to challenge the education paradigm that exists on our campus. We are a small, but we have many resourceful, passionate, and creative adults. We have the potential to create a learning environment that teaches students in a way that prepares them for the world they are entering into instead of preparing them for a world that no longer exists. We just need to figure out how. Works Cited Robinsion, K. (2010, October 14). RSA Animate - Changing Education Paradigms. Retrieved July 25, 2015. |

@npriesterA collection of my learning from SDSU EDL 680 Seminar in Personalized Learning Archives

August 2015

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed